A ‘Ballad’ writer pens a ‘song’ for migrants

A scribe cum activist, hailing from a community of ballad singers, Rejimon Kuttappan, 43, has given free rein to his storytelling skills, which he says runs in his blood.

Rejimon, who is from Pala, Central Travancore, but now settled in Thiruvananthapuram, immortalised the heroic fishermen who saved over 60,000 lives during the floods that ravaged Kerala in 2018. That turned out to be a springboard for him to launch an ‘eye opener’ of a book, which throws light on the plight of the migrants in some countries and now, before we can finish the pages of his latest ouevre, he has already started penning his third one. While writing short news stories and features are nothing new for a scribe with a decade and a half years’ experience under his belt, writing a novel is new territory. But, he seems to have taken to it like duck to water.

Real-life stories – greatest fiction

“If you have the patience to be a good reader, observer and listener, you can become a storyteller. People want to read and know about other people. And we all know that there is no great fiction like real-life stories,” Rejimon enthused.

Pocket ‘Rambo’

Rejimon has always been an activist-cum-journalist and he rises to action whenever injustice, in any form, comes to his notice. But, this has earned him more trouble than one can afford to have, yet, nothing seems to stop this defiant pocket ‘Rambo’ for the vulnerable, helpless and marginalised people out there.

Eye opener

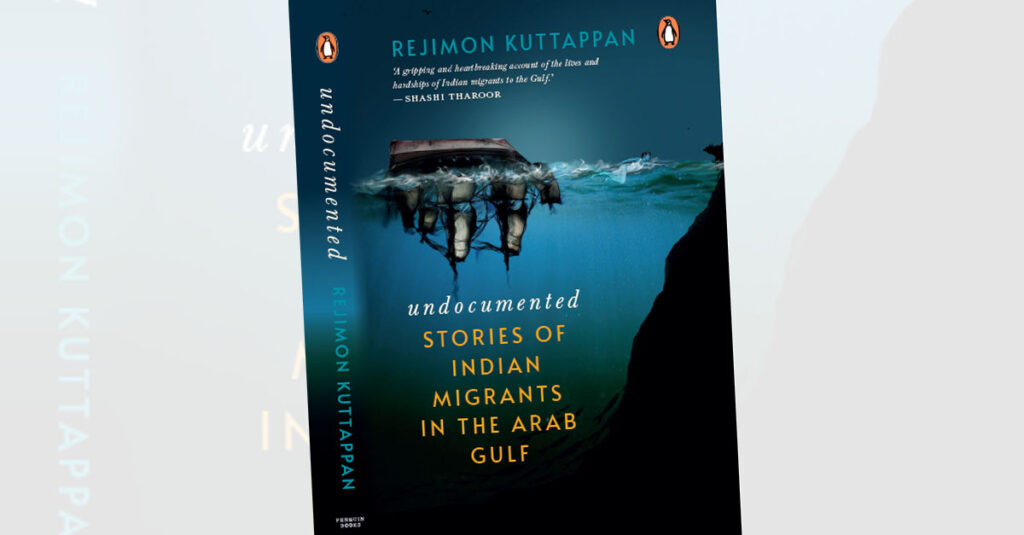

During the launch of his most recent book, Undocumented: The Stories of Indian Migrants in the Arab Gulf (2021), Dr Shashi Tharoor, author and member of the Lok Sabha from Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, commented that Undocumented “will be an eye-opener” not just in the literary world but for “many who are blissfully unaware” of the world of the marginalised, of the downtrodden, of the undocumented. In short, such an encomium, from an accomplised and exceptional wordsmith like Dr Tharoor, would rightly serve as a medal that any upcoming writer can proudly display. But, Rejimon seemed nochalant, almost detached from the excitement that his new avatar is stirring up.

Of course he is overjoyed by the fact that he has managed to bring out Undocumented, but he seems to shy away from the praise, and also does not want to draw too much attention to the fact that he has now become a published writer of two books.

“Actually, I am very new to this field. I don’t know what to tell others,” his says, his humility was in open display, when asked to comment on what he had to tell budding writers.

Excerpts:

You were and are a scribe. How did you take the next step into writing? Were you always an aspiring writer? Was this new journey a difficult transition?

I am a good listener. I can sit with anyone and anywhere to hear them. I am a decent writer and have the patience to rewrite my copies repeatedly. Moreover, I am an enthusiastic storyteller. I can be a storyteller for hours. I belong to the Dalit Panan community in Kerala. We were the ballad singers of the then royals and warriors in Kerala. I believe that my storytelling skill is in my blood. I spend a lot of time reading books and narrative long-form news stories too.

While seeing places and meeting people, I can recollect details of what I saw and talked about even after a long time and translate them into words while writing. So, producing narrative pieces wasn’t a challenge for me. I like detailing more. I am a big fan of Norman Mailer’s writing, who was a journalist, essayist, and novelist.

I can write a 350 words news story and 1,500 words long-form feature on the same subject. Somehow, I have developed that skill.

And now I have done two books. Rowing Between Rooftops: The Heroic Fishermen of the Kerala Floods (2019) and Undocumented: The Stories of Indian Migrants in the Arab Gulf (2021).

You are a scribe, a researcher, a family man (husband and father), and an activist – how did you find the time to sit and pen these books?

I had a work stint abroad, after which I returned to India and joined a migrant rights’ research organisation headquartered in the United Kingdom. As a monthly income was guaranteed from the UK organisation, along with research work and travel, I started to do long-form stories for The Caravan and global magazines. I didn’t have to meet any story target as the salary from the UK organisation was regular.

In 2018, when the floods ravaged Kerala, I filed a long-form story about heroic fishermen who saved orphans from an inundated orphanage for a foreign magazine. It was a hit. It was an exclusive one. All action of that daring rescue was captured in the story. I enjoyed talking to those daredevils and writing their heroic acts. When the story was published, I had only online access. I couldn’t get a print copy here in Kerala. The magazine was based in South East Asia. You know, these online links may go offline anytime. I realised that such heroic acts and those heroes would be forgotten in a couple of years. This made me write the book, Rowing Between Rooftops.

As I mentioned earlier, my forefathers were singers of the then warriors. I became a singer/writer of today’s heroes who saved 60,000 lives. The Indian government could save only 8,000. Writing that book gave me confidence, which ended in penning the Undocumented.

Stories of Undocumented were with me. All real-life stories. Additionally, reading, writing, meetings (regional and global) on migration gave me more understanding. I am a plotter kind of writer. I know the story. I know the angle. As mentioned earlier, I can recollect whatever I saw and talked about years before. So, I just had to sit and start writing.

As I realised that Undocumented is a serious book than the previous one, I resigned.

I got two migration research projects from two global organisations, which was enough to meet the expenses at home. And I made sure that I will be freelancing 10 stories monthly, which was enough for me to meet other expenses and focus on writing my book.

About family responsibilities, it is my wife and mother who take care of everything. I don’t even go to supermarkets to buy groceries. They know my schedules and stress. I had to attend migrant cases, travel to attend global meetings, do project research, and write stories… But I was strict about spending at least six hours a day writing the book. And I didn’t miss that schedule for six months continuously and it helped me to complete the book on time.

Did writing these books energise or exhaust you, or, are you raring for more?

I am not exhausted. I have started writing my third book.

You are young and you have already become a published author, what are the most essential ingredients that go into making a writer?

I am very new to this field. I don’t know what to tell others. What I feel is that if you have the patience to be a good reader, observer, and listener, you can become a storyteller. People want to read and know about people. And we all know that there is no great fiction like real-life stories.

Aspiring authors would love any nuggets of advice from you. What was the most difficult challenge in writing these books? Or, was it finding suitable publishers that proved to be a bigger challenge?

If you have good stories and if you know how to tell them impressively, then there are takers. In my case, I had a good pitch and a good literary agent who was impressed with my previous book. So, she managed to get Penguin.

In a world where everything from cricket to writing is looking at short, fast, and quicker versions and with the social media and internet exploding with news and whatnot at every second, do novels, fiction, non-fiction, true stories etc., that demand patience and longer reads, really have a place? Your comments.

Yes, they have a place. Yet, I feel that the number of readers are dwindling. I was a librarian during my college days in a panchayath (village council) library. Recently, I met the current librarian. “People come to the library to watch the news on TV, not to take books,” he said. I feel that reading time has increased. But mostly, it is online. Serious readers, readers who buy books, those who enjoy reading hard copies have become rare.

You have been through a lot of challenges. Has that given you the breeding ground for ideas for the stories; did the difficult experiences provide you the springboard to launch off these books?

Yes. I was often ‘punished’ for telling the truth. Only for standing up for the rights of some marginalised people. Those pushbacks helped me to realise that I am on the right path. I couldn’t tell many stories as the media freedom, in the country that I had worked in, was restricted. So, I had decided that one day I will tell the world that all is not well and our workers abroad are struggling to survive.

When did you write your first book and what is the gap between the books? How much time do you take to write these books; for instance, the latest one?

I started my first book (Rowing Between Rooftops) in 2018 September. Writing went up to February 2019. And the book hit the stores in September 2019.

In 2020 January, I talked about writing a book on labour migrants in the Arab Gulf to my literary agent Sandhya Sridhar (Zuna Literary Agency). She advised me to write down a pitch. In a few weeks, I managed to make one. And in a few days, she managed to get Penguin. They asked for two sample chapters. By mid February, I emailed those two chapters and the pitch. They were impressed with the stories and send me a contract. I signed it. The deadline was September 2020 and I managed to meet the deadline. The manuscript was sent. And after that every week we had email conversations for editing, legal vetting, cover design, proofreading, and all in addition to getting endorsements from Dr Shashi Tharoor, Ashley William Gois (Migrant Forum in Asia – MFA – regional coordinator) and Dr Rajai Ray Jureidini (professor at Qatar Hamad bin Khalifa University).

The book was released on November 15, this year. And on November 23, Dr Shashi Tharoor, author, MP, released the book officially.

As a journalist and writer, you champion the underdog; the underprivileged; the marginalised… is this because that you have a spirited activist blood in you, or is it just that you stumbled on this fount of stories and decide to promote them? What exactly makes your blood boil and is writing a catharsis for all the pent-up emotions?

My first byline was for reporting the death of a medic in Kerala who took a different path which earned him respect. He was very young. He was a rank holder. But he didn’t migrate to America or Europe. Instead, he moved to a tribal area in the Western Ghats and practiced there at a government primary health center. When he left the world, shocking everybody, the tribal elders came to the hospital and performed rituals and honoured his service.

I reported the story of how the tribals loved that young doctor and how lost they felt without him. The story was an anchor story of The New Indian Express front page in the Kerala edition.

That story became viral. This is in 2005. TV channels started to contact me to get more details of the story. I realised that his commitment towards society, marginalised and downtrodden earned him respect. He proved that a doctor can do great deeds to society. So, it set me thinking: why can’t I? And we, being journalists, can do more, isn’t it? So, I started to look for untold stories. I started to tell stories of the marginalised and the downtrodden. I was into activism in my school days. I had built smokeless stoves for slum-dwellers. I had been a literacy instructor too with the literacy mission. In 1994, I was selected as the best literacy instructor in Kerala, when I was 15. These things have helped me to do responsible journalism.

Is this world only for the rich, for those with high-placed connections, power, and political friends? Can the ones who have nothing, but just innocence and truth in their hands ever win? Is there a place for simple, harmless, and peaceful folks in this world – and what would you call that?

The place for simple, harmless, and peaceful folks in this world is shrinking. Chances for the ones who have nothing, but just innocence and truth in their hands, to ever win, are less.

Do you think words have the power to change this world? At least a bit?

Yes, a bit is possible. And I have witnessed and experienced that. When my story exposed human trafficking, even though I faced the consequences for that, the authorities concerned started to view the issue seriously and decided to take some measures to stop it.

What was the most unbearable incident that you have faced in your career thus far and have you been the better or worse for it?

Being ‘punished’ for telling the truth. Being arrested at an airport and detained for 12 hours for surveying workers in a previous visit to a country on the subject of workers’ rights. I have faced challenges only in telling the truth and doing responsible journalism. However, I am not regretting that.

Is there money in writing, especially in India (for Indian authors)?

I am not aware of those things as I am a fresher.

There must be a motive, an aim, or a plan with each book you have authored. Do you feel that you have achieved that particular mission with your two books?

Yes, the aim of writing Rowing Between Rooftops was to record the names of heroic fishermen and their daredevilry so that people don’t forget them. Even in the Kerala Assembly library, the book has found a place. Interestingly, a Ph.D. student at Coimbatore University has used this book for his thesis.

The aim of writing Undocumented is to tell the world that our migrant workers in some countries are like slaves and more has to be done for the protection and welfare of their rights. I am waiting to see the impact. During the launch, Dr Tharoor commented that this book will be an eye-opener.

What kind of world do you want to see in the next decade?

Workers getting decent working conditions and their rights being honoured.

What next (as far as writing is concerned)?

Writing a book on Adyakka Raju, a Keralite thief, and witness in Sister Abhaya’s murder case. The case is the longest one in India’s judicial history — 28 years. Despite being tortured physically and mentally till now, he stood up and told the truth in court.

About:

Right from his school days, Rejimon was more into reading newspapers and magazines. Those days, glossy pages were less, but there were more articles. “Those stories encouraged me to do journalism. I wanted to tell stories. However, my parents wanted me to become either a banker or a scientist. As they wished, I completed my masters’ in applied physics. Despite getting 70 percent in MSc, I didn’t pursue anything in that line,” says Rejimon who, as a writer, is adept in both English and Malayalam.

Rejimon’s father was a banker. He passed away in 2017. “My father didn’t wait to see my books. I miss him. I have kept the copies of the book for him in front of his photo,” Rejimon said, adding that his mother was a homemaker and living with him and his wife and two sons, Rishikesh, 12 and Kasinath, 10. “Without my wife’s support, I wouldn’t have written these books,” Rejimon said.

0 Comments